Larger than the global stock market in value, bonds are one of the most traded financial assets in the world. Discover more about what bonds are, and how they work.

What is a bond?

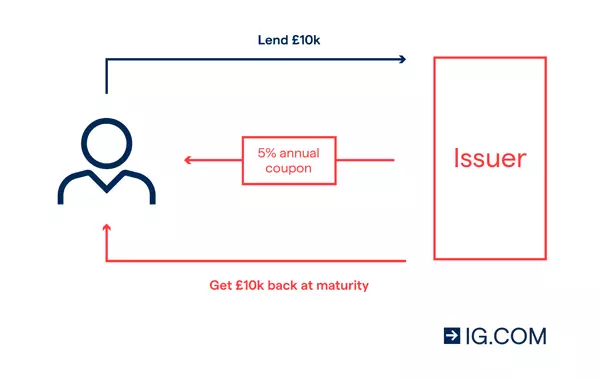

A bond is a type of loan in which the bondholder lends money to a company or government. The borrower makes regular interest payments until a set date in the future, when they repay the initial loan amount.

This final amount paid back by the bond issuer to the bondholder is called the ‘principal’, and the interest is a series of payments called the ‘coupon’.

The principal may also be referred to as the face value, or par value, of the bond. Coupons are paid at set intervals (eg semi-annually, annually or, in some cases, monthly), and are a percentage of the principal. Coupon amounts are typically fixed but, as is the case for index-linked bonds, these can vary as the bond adjusts its payments to follow the movements of an index – like the inflation rate.

As bonds are generally negotiable securities, they can be bought and sold like stocks in a secondary market, though there are significant differences between the two. Although several bonds list on exchanges like the London Stock Exchange (LSE), they are primarily traded over-the-counter (OTC) through institutional broker-dealers.

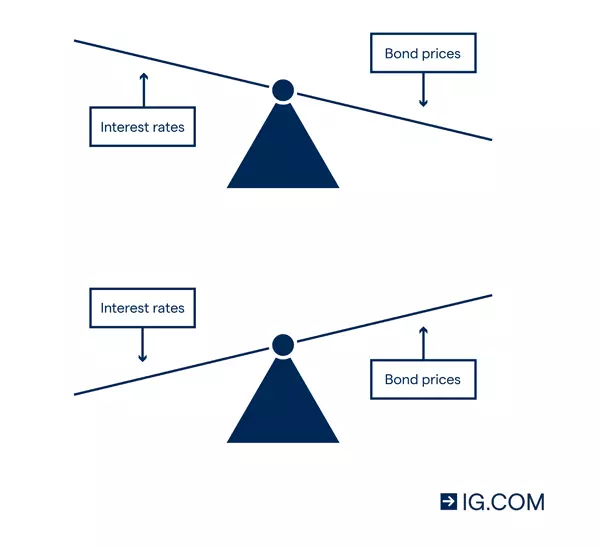

Like stocks, bond prices are subject to the market forces of supply and demand. This means that investors can earn a profit if the asset appreciates in value, or cut a loss if a bond they sell has depreciated. Because a bond is a debt instrument, its price is highly dependent on interest rates.

When interest rates increase, bonds become less attractive to investors who could be earning high interest elsewhere, and prices drop. Likewise, when interest rates decrease, bonds become more attractive and prices rise.

What type of bonds are there?

A wide variety of bonds available. In practice, bonds are frequently defined by the identity of their issuer – governments, corporations, municipalities and governmental agencies. When needing to raise capital for investment or to support current expenditure, issuers may find more favourable interest rates and terms in the bond market than those offered by other credit channels like banks.

These are the four major bond types:

Government bonds

In the UK, government-issued bonds are known as gilts. In the US, they’re called Treasuries. While all investment incurs risk, sovereign bonds from established and stable economies are regarded as being

low risk.

US Treasury bills (or T-bills) are bonds with a maturity of one year or less; Treasury notes (T-notes) have a maturity of between two and ten years; and Treasury bonds (T-bonds) have terms of 30 years.

Whereas the majority of government-issued bonds in the UK and US have a fixed interest rate, both offer types that vary the coupon payment based on inflation. In the UK, these are Index-linked gilts, and in the US, they are Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS).

Corporate bonds

Corporate bonds are issued by corporations to secure funding for investment. Although high-quality bonds from well-established companies are seen as a conservative investment, they still incur more risk than government bonds, and pay higher interest.

When you buy a corporate bond, you become a creditor and enjoy more protection from loss than shareholders – ie if the company is liquidated, bondholders are compensated before shareholders. Corporate bonds are evaluated by ratings agencies like Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch Ratings.

Municipal bonds

Municipal bonds, or ‘munis’, are used by local government authorities (like councils, municipalities, cities or districts) to finance local infrastructure projects. In the UK, they are issued by the UK Municipal Bonds Agency (UK MBA).

Like government bonds, they are considered low-risk investments and offer a comparatively low interest rate. In the US, municipal bonds may be exempt from certain taxes at both the local, state and federal levels.

Agency bonds

Primarily a US phenomenon, agency bonds are securities issued by either government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) or government departments other than the Treasury. Whereas the federal government agency bonds are backed by the US government, GSE bonds are not. Well-known GSE bonds include those of the National Mortgage Association (‘Fannie Mae’) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage (‘Freddie Mac’).

How do bonds work?

Bonds are debt instruments. The bondholder loans capital to the issuer, who then repays the loan in a manner outlined by the bond. Often, the issuer makes a series of fixed interest payments – coupons – on a regular basis. The principal amount of the loan is then repaid last, when the bond reaches its maturity or expiration date.

There are variations to this pattern, however, including zero-coupon bonds and index-linked gilts.

- Zero-coupon bonds: these make no coupon payments. Instead, the interest on the bond is the difference between the price of the bond and the principal (or face value). For example, if you bought the bond for £950 and received its face value of £1000 at maturity, you have earned 5.26% interest

- Index-linked gilts: these vary coupon payments according to fluctuations in the rate of inflation. Although the changes to the coupon rates are calculated differently, the US equivalents are Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS)

Learn more about buying bonds on our platform

Bond characteristics

Maturity and duration

A bond should specify both its maturity (or term) and its duration. The two are very different. A bond’s time to maturity is the length of time until it expires and it makes its final payment – ie its active lifespan.

Duration specifies two significant characteristics of a bond. Firstly, ‘Macaulay duration’ is the amount of time the bond takes to repay its principal and is expressed as a number of years. This is converted into the bond’s ‘modified duration’ – a measure of its price sensitivity to changes in the interest rate. The longer the bond’s maturity, the more its price will fluctuate with movements in interest rates.

Credit rating

Rating agencies like Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch assess the creditworthiness of bond issuers, thereby giving market participants valuable insight into the bond’s credit risk. This is vital for both issuers and potential buyers.

Buyers need to know if the issuer is in a good position to make coupon and principal repayments consistently and timeously. Issuers can likewise use the rating to price their bonds at a level that should attract investors.

The lower the issuer’s credit risk – or the higher their rating – the lower they can set their coupon rates, reducing the cost of borrowing. Conversely, the higher the issuer’s credit risk, the higher their yields will need to be to attract investors.

To use Fitch Ratings’ scale as an example, the lowest risk long-term bonds are given a AAA rating, while sub-investment grade (or ‘junk bonds’) begin at BB+.

Face value and issue price

The face value of a bond is the principal amount it agrees to pay the bondholder, excluding coupons. In general, this is paid as a lump sum when the bond matures or expires, and remains unchanged throughout the bond’s lifespan. This isn’t always the case, though. For example, certain index-linked bonds like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) adjust the face value in line with inflation.

In theory, and with the exception of zero-coupon bonds, the issue price should equal a bond’s face value. This is because the face value equals the full value of the loan, which is paid to the issuer when the bond is bought. However, the price of a bond on the secondary market – after it has been issued – can fluctuate substantially depending on a variety of factors.

Zero-coupon bonds make no coupon payments, which means that in order to pay interest, the issue price is below the bond’s face value.

Coupon rate and coupon dates

The coupon rate of a bond is the relation between the value of the bond’s coupon payments and its face value, expressed as a percentage. For example, if the face value of a bond is £1000 and it pays an annual coupon of £50, its coupon rate is 5% per annum. Traditionally, coupon rates are annualised, so two payments of £25 will also return a 5% coupon rate.

A bond’s coupon rate must be differentiated from current yield and yield to maturity.

- Current yield is the interest earned on the bond’s current market price via its annual coupon payments

- Yield to maturity is a more complex calculation, and expresses the total interest earned on the bond’s current market price over the remainder of its lifespan, and includes all future coupon payments and the principal amount

Coupon dates are the dates on which the bond issuer is required to pay the coupon. The bond will specify these, but as a matter of course, coupons are paid annually, semi-annually, quarterly or monthly. Bond prices can be quoted as ex-coupon or cum-coupon. When ex-coupon, the price excludes the next coupon payment; when cum-coupon, the price includes the next payment.

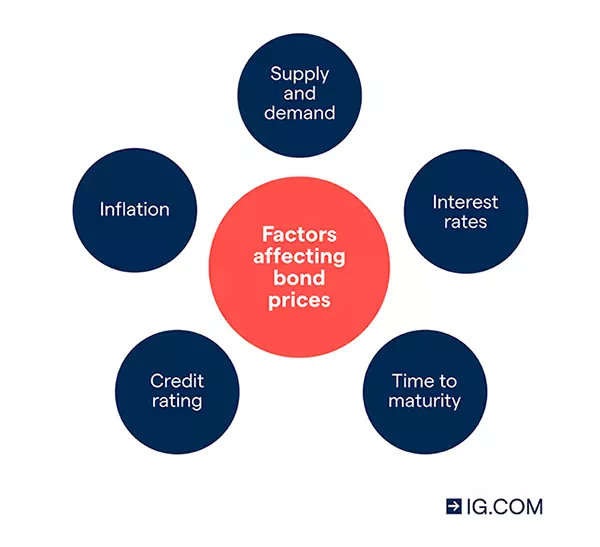

What affects the prices of bonds?

- Supply and demand

- How close the bond is to maturity

- Credit ratings

- Inflation

Supply and demand

Just like any tradable asset, bond prices are subject to the forces of supply and demand. The supply of bonds is dependent on issuing organisations and their need for funds. Demand is determined by a bond’s attractiveness as an investment – relative to alternative opportunities. Interest rates play a decisive role in determining supply and demand, and we explore the relationship between interest and bond prices in greater detail below.

How close the bond is to maturity

Newly-issued bonds will always be priced with current interest rates in mind, meaning that they’ll usually trade at or near their par or face value. And by the time a bond has reached maturity, it’s just a pay out of the original loan – meaning that a bond will move back towards its par value as it nears this point. The number of interest rate payments remaining before a bond matures will also have an impact on its price.

Credit ratings

Although bonds may often be seen as conservative investment vehicles, defaults can still happen. A riskier bond will usually trade at a lower price than a bond with lower risk and a similar interest rate. As mentioned, the main way of assessing the risk of a bond issuer defaulting is through its rating from the three main credit rating agencies – Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch.

Inflation

High inflation is usually bad news for bondholders. This can be attributed to two factors:

- A bond’s fixed coupon payment amount become less valuable to investors when money loses its purchasing power

- Central monetary authorities like the Bank of England (BoE) often react to high inflation by raising interest rates. As interest rates and bond prices are inversely related, the higher interest rates result in a lower market price for the bond

Bond prices and interest rates

Interest rates can have a major impact on both the supply and demand for bonds. If interest rates are lower than the coupon rate on a bond, demand for that bond will rise as it represents a better investment. On the other hand, if interest rates rise above the coupon rate of the bond, demand will drop.

Similarly, bond issuers may constrain their supply if interest rates are too high to make borrowing an affordable source of capital. The rule of thumb is that interest rates and bond prices are inversely correlated – as one rises, so the other falls.

When deciding how you would like to trade or invest in bonds, it’s crucial to understand how interest rates will affect your overall strategy.

Bond prices and the Fed

As the Federal Reserve is the monetary authority of the world’s largest economy, the policy decisions it makes have global repercussions. When the Fed drops interest rates, for example, demand in the very large market for ten-year Treasury notes (T-notes) increases as those issued with coupon rates above the general interest rate become attractive to investors.

Institutional investors with significant holdings of T-notes, such as pension funds, mutual funds, ETFs and investment banks and trusts, will see an appreciation of their assets with the rise in T-note and other bond prices.

Bond examples

- UK Treasury Gilt

- Zero-coupon bond

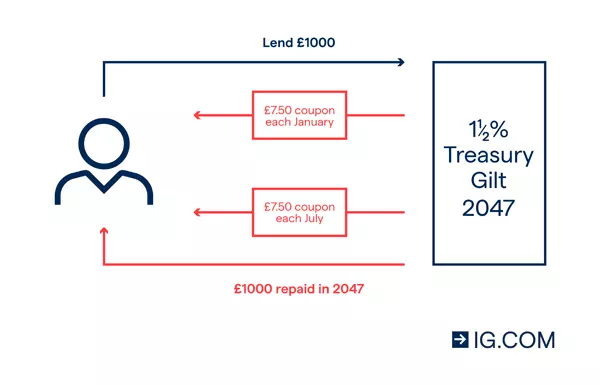

An example of a conventional UK government gilt is the ‘1½% Treasury Gilt 2047’. Here, you would receive two equal coupon payments per year, exactly six months apart (unless these dates fall on a non-business day, in which case they roll over to the next business day).

The date of maturity on the bond is 2047, and the coupon rate is 1.5% per year. If you held £1000 nominal of 1½% Treasury Gilt 2047, you would receive two coupon payments of £7.50 each on 22 January and 22 July.

Consider the case of a zero-coupon bond that matures in a year. The bond makes no coupon payments, and instead pays interest by discounting the issue price of the bond to a lower value than its par value.

Here, we’ll assume that the general interest rate for a comparative risk level is 5.26%. To be competitive, if the par value of the bond is £1000, the issuer will have to set a price of £950.

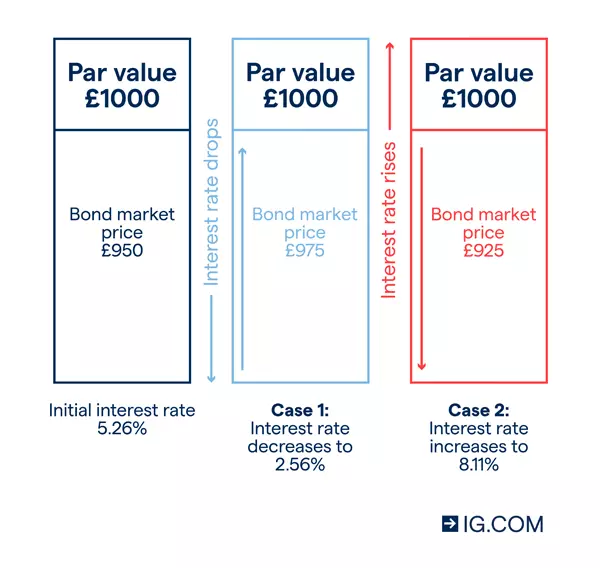

If you, as the bondholder, decide to sell the bond before it matures, you can earn a profit if the general interest rate for the same risk level has decreased in the interim.

At a prevailing interest rate of 2.56%, you could sell the bond for £975. The inverse of this is also true, and if the prevailing rate of interest rose to 8.11%, your bond would have a market price of £925.

What are the risks of bonds?

Credit risk

Credit risk is the risk that the bond issuer will not be in a position to make coupon or principal repayments in full and on time. In a worst case scenario, the debtor could default completely. Ratings agencies assess creditworthiness and rank issuers accordingly.

Interest rate risk

Interest rate risk is the potential that rising interest rates will cause the value of your bond to fall. This is because of the effect that high rates have on the opportunity cost of holding a bond when you could get a better return elsewhere.

Inflation risk

Inflation risk refers to the possibility that rising inflation will cause the value of your bond to fall. If the rate of inflation rises over the coupon rate of your bond, then your investment will lose money in real terms. Index-linked bonds can help mitigate this risk.

Liquidity risk

Liquidity risk is the chance that a market may not have enough buyers to purchase your bond holdings quickly, and at the current price. If you need to sell rapidly, you may need to drop your price.

Currency risk

Currency risk only applies if you buy a bond that pays out in a different currency to your reference currency. If you do this, then fluctuating exchange rates may see the value of your investment drop.

Call risk

Call risk occurs when the bond issuer has a right, but not the obligation, to repay the face value of the bond before its official expiry date. The absence of the remaining coupon payments could result in a loss of fixed-income, or possibly a lower yield to maturity on the investment.

FAQs

How do bonds work?

A bond is type of loan in which the bond issuer owes the bondholder a repayment of the principal amount, in addition to interest. Whereas the principal is usually the final payment from the bond issuer to the holder, the interest on this amount is often a series of payments called the ‘coupon’.

As bonds are generally negotiable securities, they can be bought and sold like stocks in a secondary market, though there are significant differences between the two. Although several bonds list on an exchange, they are primarily traded over-the-counter (OTC) through institutional broker-dealers.

Are bonds a good investment?

Highly-quality bonds are generally considered to be low-risk investments. This means that their interest rates are also often comparatively low. Whereas bonds with comparatively high coupon rates are available, these incur greater risk. Traditionally, investors look to bonds to diversify their portfolio holdings and to hedge against downturns in equity markets.

What's an example of a bond?

An example of a conventional UK government gilt is the ‘1½% Treasury Gilt 2047’. Here, you would receive two equal coupon payments per year, exactly six months apart (unless these dates fall on a non-business day, in which case they roll over to the next business day).

The date of maturity on the bond is 2047, and the coupon rate is 1.5% per year. If you held £1000 nominal of 1½% Treasury Gilt 2047, you would receive two coupon payments of £7.50 each on 22 January and 22 July.

Are bonds guaranteed?

‘Guaranteed bonds’ are bonds whose principal and coupon payments are guaranteed by a third party, such as an insurance company, government or parent corporation. They include corporate and municipal bonds.

Sovereign bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and backing of their respective governments. It is important to note that even guaranteed bonds are subject to numerous risks, including credit risk.

What is the riskiest type of bond?

Bonds with low creditworthiness are the most risky. Generally, corporate bonds are considered to be more risky than those issued by stable governments in well-functioning economies. Corporate bondholders do nonetheless have greater protection than equity holders – in the case of insolvency, bond debt is senior to shareholder claims

What is the safest type of bond?

Bonds with high creditworthiness are the safest. Generally, government bonds are seen as a safer alternative to corporate bonds.

What makes a bond attractive?

The balance between the bond’s credit rating – ie its credit risk level – and its yield to maturity combine to make for an attractive investment opportunity. If the yield to maturity for a given level of risk is greater than the interest for an equivalent risk elsewhere, the bond will be sought after.

Are bonds safe in market crashes?

Government bonds stand to fare better in market crashes than corporate bonds, but the relationship between equity market performance and bonds is complex. If corporations become insolvent due to a market crash, their bondholders could possibly receive back less than the principal. A market crash may well also see a flight of capital into more conservative investments, increasing the demand for government bonds.

Are bonds risk free?

No bond is risk-free. All bonds are subject to interest rate risk, inflation risk and liquidity risk. Whereas government bonds may sometimes be described as risk-free as they are issued by highly creditworthy institutions, even these carry an element of default risk.