What is Brexit?

The UK legally departed the EU on 31 January 2020, and the economic severance was finalised on 31 December 2020. Here, we explain everything you need to know about Brexit, including what happens next.

Brexit definition

‘Brexit’ is a contraction of ‘British exit’, and it is the word used to define the UK’s departure from the EU.

Brexit: what next?

Brexit is completed and the UK has left the EU, so what happens now? Because the two parties were able to reach a deal, the UK’s departure was on better terms than would’ve been possible if a deal hadn’t been completed. We’ve gone through the main sticking points of the deal below.

Trade

There aren’t any tariffs or limits on trade quotas between the UK and EU, but some new checks and customs declarations will be implemented at borders. Plus, there are some new restrictions on UK food items going into the EU – like uncooked meats having to be frozen to -18 degrees Celsius before they can cross the border.

Travel

UK nationals can still travel to the EU, but they will need a visa if they stay for more than 90 days in a 180-day period. Plus, EU pet passports will no longer be valid. Instead, UK nationals will have to obtain an animal health certificate (AHC) before their pet can travel with them to the continent.

Fishing

Over five and a half years from January 2021, the UK will gradually gain greater control over its fisheries. The deal still allows EU boats to fish in UK waters, but UK ships will steadily gain a greater proportion of the quota – with most of it being transferred to British ships in 2021. After 2026, there will be annual negotiations to decide how much of the annual quota is allocated to British ships and how much is allocated to EU ships. After 2026, if it so wished, the UK could totally exclude EU vessels from fishing in its waters, but there would likely be repercussions from the EU.

Education

The UK doesn’t have a place in the Erasmus exchange programme with EU countries, so British students may find it more difficult to study in the EU. This change does not apply to students in Northern Ireland. The British government has announced a new exchange scheme – starting in September 2021 – which will be similar to Erasmus but will apply to students from around the world.

The ECJ

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) no longer has any role in the British legal system. In the event of any disputes between UK courts and the ECJ, cases will be referred to an independent tribunal. But, the ECJ can still play a role in Northern Ireland since it continues to follow some EU trade rules.

Security and data

The UK no longer has automatic access to security databases like those at Europol but it can access them on request. The arrangement between UK and EU security forces is similar to the access enjoyed by the US.

Get Brexit-ready with IG

Discover trading opportunities around Brexit – and download our free checklist – to learn how to profit from upcoming volatility and hedge against downside risk.

Brexit referendum is held – June 2016

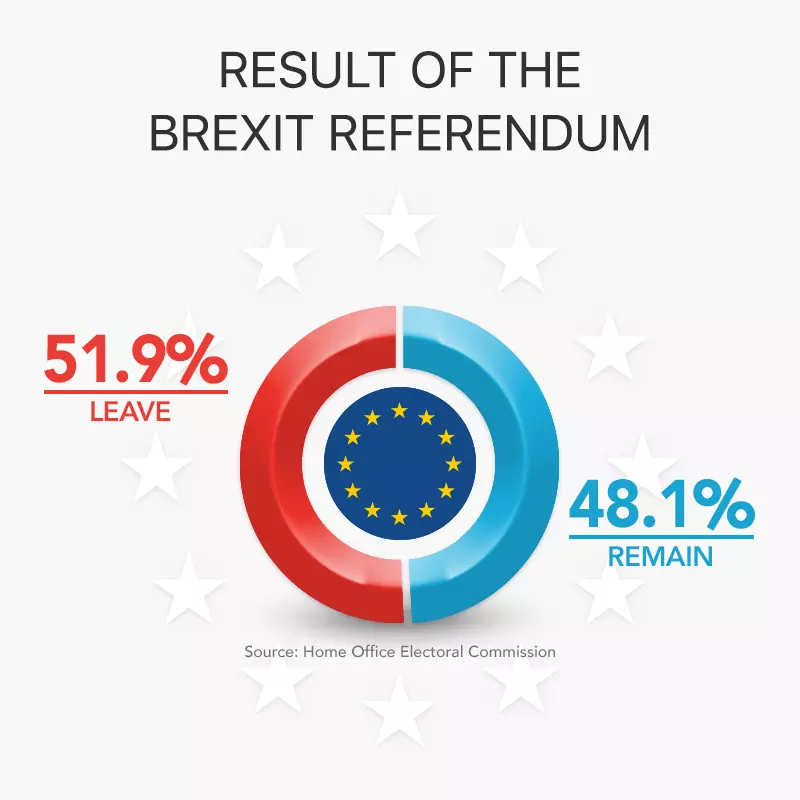

The referendum held in 2016 saw over 30 million people turn up to vote. The split was 51.9% in favour to leave, 48.1% in favour of remain.

There was significant regional variation in the vote: England and Wales voted to leave, while Northern Ireland and Scotland voted to remain. The majority in favour of either option was largest in Scotland, while the result was closest in Wales. Turnout in the referendum was high, at 72.2%. All in all, the vote revealed a deeply divided Britain: a fact which defined the following months of negotiations, challenges and reprisals.

| Region | Leave vote share | Remain vote share | Leave/ Remain | Turnout |

| England | 53.4% | 46.6% | Leave | 73% |

| Northern Ireland | 44.2% | 55.8% | Remain | 62.7% |

| Scotland | 38% | 62% | Remain | 67.2% |

| Wales | 52.5% | 47.5% | Leave | 71.7% |

The result took the government by surprise. David Cameron resigned from number 10, and was replaced by Theresa May following a leadership contest within the Conservative Party. She confirmed that the UK would leave the EU with her famous ‘Brexit means Brexit’ soundbite, despite being in favour of remain before the result was announced.

Article 50 is triggered – March 2017

Article 50 was triggered on 29 March 2017, starting the official two-year countdown to Brexit. What followed was a period of planning by EU and UK negotiators, lasting until June 2017 when negotiations began. In the interim, Theresa May called a snap election, hoping to boost the Tory’s parliamentary majority and strengthen the government’s bargaining power with EU leaders.

The plan backfired spectacularly, as the Conservatives lost their majority and were forced to form a coalition with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Some argue this has weakened the government’s position considerably, as ratification of the final deal will require the backing of the DUP in parliament.

Brexit negotiations begin – June 2017

Negotiations officially began on 19 June 2017, with the UK accepting a phased negotiation timeline suggested by Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief negotiator. Phase one concluded in December 2017, with agreements in place regarding a financial settlement of between £35-39 billion, a soft Irish border, as well as the rights of UK and EU citizens living cross-border.

Phase two ran until mid-November 2018 and focused on the future relationship between the UK and the EU. As part of this phase of negotiations, a transition period of 21 months was provisionally agreed, which is scheduled to start immediately after the leave date. This will give time for the UK to negotiate its future trading relationship with the EU.

The Chequers deal is published – July 2018

The ‘Chequers deal’ – published on 12 July 2018 – was one of the most substantial and most complete plans for Britain’s exit from the EU at the time. It set out the relationship that the UK would seek with the EU following its departure from the union.

Although being approved by the British cabinet, the plan was rejected by the EU in September 2018. Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief negotiator, cited that the integrity of the EU single market was not negotiable and that the UK cannot ‘cherry pick’ the parts of the single market it likes. The single market is reliant on ‘four freedoms’: the free movement of goods, labour, services and capital. The Chequers agreement only made concessions for the free movement of goods, which prompted Barnier’s comments.

The major sticking point was how the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland would work in practice, particularly if the two sides were unable to agree a workable trade deal during the transition phase. This is because the EU is unable to accept a soft border with a country that has different customs arrangements.

Theresa May puts her draft deal to cabinet – November 2018

After many months of negotiation, Theresa May finally put a draft deal – a successor to the failed Chequers agreement – to her cabinet in November 2018. The new deal represented a step towards a soft Brexit, as it detailed a plan for trade during the transition period, the Irish border, the rights of UK and EU citizens.

The prime minister declared that the cabinet had accepted her deal ‘collectively’ following around five hours of discussions on 14 November 2018. However, this terminology implied that the decision was not unanimous, with reports later suggesting that up to ten ministers had criticised the prime minister’s plan – particularly the Irish backstop. Several cabinet members resigned immediately, including Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab. Many other MPs also expressed concerns over the proposed deal.

On 25 November 2018, a summit of EU leaders agreed to the prime minister’s deal. After the announcement, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker stated that the decision was ‘not a moment of jubilation but a moment of deep sadness’ in light of Britain’s seemingly solidified departure.

Theresa May’s deal goes to a Commons vote – December 2018

On 10 December 2018, one day before the House of Commons was set to vote on the prime minister’s deal, Theresa May decided to postpone the vote in lieu of serious opposition from both sides of the aisle and speculation the deal would be rejected by the House.

The prime minister promised to return to Brussels to seek assurances from EU leaders on certain aspects of her deal – particularly with regard to clarification on the Irish backstop and whether the UK would be tied indefinitely to a customs union with the EU.

Vote of confidence in Theresa May – December 2018

On 12 December, a vote of confidence in Theresa May was brought forward by her own party. The vote saw 117 Conservative MPs move against her, but she prevailed with 200 voting in her favour.

Theresa May’s deal is defeated – January 2019

Following the delay of the first vote, it was rescheduled for 15 January 2019. The prime minister’s deal was historically defeated by 432 votes to 202 in the Commons, as had been expected at the time of the first scheduled vote. Her deal included plans for the rights of UK citizens living in the EU and EU citizens living in the UK, as well as for the transition period, a divorce settlement of £39 billion, and a contentious plan for the Irish border.

Many MPs said that the prime minister’s draft agreement was simply a bad deal and that they could not in good conscience give it their support. Because of the thumping defeat, Jeremy Corbyn triggered a vote of no confidence in the government, which took place on 16 January 2019.

Vote of no confidence in the government – January 2019

Theresa May survived a vote of no confidence in her government on 16 January 2019. The result was 325 to 306, a closer margin than was expected. The DUP were key to her victory as it is likely that the government would have lost the vote had its ten MPs rebelled.

Theresa May comes up with ‘Plan B’ – January 2019

Following the defeat of her Brexit plan on 15 January 2019, the prime minister had three parliamentary working days to put forward a ‘Plan B’. Her proposal – presented on 21 January 2019 – proved similar to the rejected deal, with only very minor tweaks. However, the prime minister promised to look again at the contentious Irish backstop with a view to getting the deal through the Commons.

Theresa May’s deal is defeated for a second time – March 2019

Theresa May’s Brexit deal was rejected for a second time on 12 March 2019. While the majority – 391 to 242 – was not as crushing as the vote of 15 January, it still constituted a decisive defeat for the prime minister’s efforts in her Brexit negotiations.

MPs express their desire to avoid no-deal Brexit – March 2019

On 13 March, MPs voted by 321 to 278 in a motion to avoid a no-deal departure. While this vote was not legally binding on the EU or its member states, it indicated that there was strong support for a final deal to be reached before the UK leaves the bloc.

MPs express their desire to extend article 50 – March 2019

On 14 March, MPs voted by 413 to 202 to seek an extension to article 50. Theresa May subsequently returned to EU leaders to seek this extension, which she secured.

First round of indicative votes held in the Commons – March 2019

A series of indicative votes was held on 27 March with the aim of highlighting which option had the most support from the Commons. While no option was able to command a majority, a second referendum had the most support.

However, whether a second referendum will take place remains to be seen, and it is a highly contentious issue – seen by many to be flying in the face of the initial referendum result.

Theresa May’s deal is defeated for a third time – March 2019

In a move which shocked few within her own party, the prime minister met with her backbench MPs and ministers at the 1922 Committee on 27 March, the same day as the indicative votes. She promised that, should her party get behind her deal, she would step down. This would allow for someone else to lead negotiations on the UK’s future relationship from the EU – most likely a Brexiteer – during the transition period.

However, Theresa May’s Brexit deal was defeated for a third time on 29 March, by a margin of 344 to 286.

Second round of indicative votes held in the Commons – April 2019

There was a second round of indicative votes held on 1 April which were aimed at identifying a majority for the most popular options proposed on 27 March. The most popular was a confirmatory referendum with 280 voting in favour – though this was not enough for a majority with 292 voting against. Meanwhile, a customs union narrowly missed out on a majority, losing by three votes.

The two other options were for common market 2.0 – a proposal to join the single market and a customs union – which was defeated by 21 votes, and a vote proposed by MP Joanna Cherry which would give MPs the power to block no deal by revoking article 50. This proposal was the least popular of the night, with just 191 MPs voting in favour of it and 292 voting against.

Cooper-Letwin amendment is passed – April 2019

On 3 April, MPs voted by 313 to 312 to pass the Cooper-Letwin amendment which would seek a further extension to article 50 to avoid no deal. The vote represented the first indicative vote which was able to secure a majority in the Commons – though the result is not legally binding on the EU.

Theresa May requests another article 50 extension – April 2019

With the 12 April deadline fast approaching – and with no new developments coming from the Commons – Theresa May wrote to Donald Tusk on 5 April, requesting that the deadline for the UK’s departure be extended to 30 June 2019. In her request, the prime minister made clear that should a deal be passed before 22 May, the UK would not hold European elections, but that the necessary preparations are being made in the event that these elections need to be held.

Equally, EU diplomats stated that even if the UK was bound to hold European elections, the UK could withdraw its MEPs once a final deal had been approved by the Commons. Their space in the European Parliament would be filled by delegates from the remaining 27 European member states.

The Brexit deadline is pushed back to 31 October – April 2019

Following a meeting of European leaders on 10 April, it was agreed that the deadline for the UK’s departure from the bloc would be pushed back to 31 October – a full seven months past the initial 29 March deadline.

The UK will be allowed to leave the EU before 31 October, but only if the House of Commons approves the prime minister’s withdrawal agreement.

Theresa May confirms a fourth vote – May 2019

On 21 May, the prime minister announced that she would put her vote to a fourth – and in the eyes of many commentators, final – round of debate in the Commons. She did so in the face of opposition from her own party – with the 1922 Committee and the European Research Group (ERG) voicing strong criticism of the prime minister’s deal, and with some Conservative MPs calling for her resignation.

This criticism grew so strong that Theresa May decided to postpone the vote – which was initially scheduled for the start of June 2019. As a result, a shadow was cast over the future of her premiership – with many in the media beginning to count her remaining time as prime minister in days rather than months.

Theresa May announces that she will resign – May 2019

With no clear or amicable way forward, Theresa May announced that she would resign on 7 June 2019 in light of what many called a failure to deliver Brexit. She promised to remain on as a caretaker prime minister until the result of the leadership contest was announced on 23 July 2019.

Following the vote, Theresa May went to Buckingham Palace to formally tender her resignation to the Queen and set the stage for her predecessor to take over.

Boris Johnson becomes prime minister – July 2019

After a hotly contested leadership race, Boris Johnson emerged victorious from an initially saturated field of candidates. He secured Britain’s top job with 92,153 votes from Conservative Party members out of a possible 159,320. His opponent in the final two, Jeremy Hunt, secured 46,656.

Parliament prorogued – September 2019

A little over a month into Boris Johnson’s premiership, he announced that he would be proroguing (suspending) parliament at the close of business on 9 September to prepare for a Queen’s Speech and the formal opening of a new parliamentary session on 14 October. Many criticised the prime minister for suspending parliament so close to the departure date of 31 October and said that it was a way for him to bulldoze through his Brexit plan without interference.

MPs vote to block no deal – September 2019

MPs voted on 9 September, before the prorogation came into effect, to prevent a no-deal Brexit. The result of the vote represented a significant loss to Johnson, who now has until 19 October to get a new deal passed in parliament, or to get MPs to back a no-deal Brexit.

If this deadline passes with both of these options being rejected, the prime minister will have to request an extension to the UK’s departure date until 31 January 2020.

Parliament resumes after prorogation ruled unlawful – September 2019

Following the prorogation of parliament, opposition to the decision by Johnson became so fierce that a legal challenge was submitted to the Supreme Court to get the suspension of parliament overruled. A decision was reached on 24 September, in which the 11 justices unanimously declared that the prorogation had been unlawful, meaning parliament was free to resume.

PM submits new plans to Brussels and prorogues parliament – October 2019

Boris Johnson submitted what some called a last-ditch plan to the EU in early October, in an attempt to resolve the Irish border issue. The prime minister’s plan is for Northern Ireland to stay in the EU customs union for all industrial and agricultural goods. This arrangement would be subject to the approval of the Northern Ireland Assembly in Stormont, which would need to approve it for a transition period and then every four years.

However, for all other industries, Northern Ireland would leave the EU customs union, while the rest of the UK will leave the EU customs union entirely. Theoretically, this would eliminate lengthy delays at border checkpoints on the island of Ireland. The plan was received with apprehension in the EU, but European leaders recognised the concessions made by the British government.

Following the submittal of his new Brexit plan, the prime minister prorogued parliament on 8 October to allow the government time to prepare for a Queen’s speech and the beginning of a new parliamentary session, which took place on 14 October. The parliamentary session before this prorogation was the longest in British history, lasting 839 days.

Boris Johnson agrees Brexit deal with the EU – October 2019

A Brexit deal was agreed between Prime Minister Boris Johnson and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker on 17 October. The deal is a modified version of the prime minister’s earlier proposal, which removes the Irish backstop – one of the most contentious talking points in previous versions of the withdrawal agreement.

Instead, Northern Ireland will remain in the UK customs territory and, at the same time, be classified as a point of entry into the EU customs union. Under the agreement, the UK will not enforce tariffs to products entering Northern Ireland, so long as they are not intended for shipment across the Irish border.

This arrangement will be up for review every four years by Stormont, at which point there will be a vote to decide whether to continue with the trade arrangements or not. Unlike other votes in Northern Ireland, this will only require a simple majority to pass, rather than the usual majority in both the unionist and nationalist parties.

Commons grants assent for withdrawal agreement bill to be debated during second reading – October 2019

The Commons granted assent for Boris Johnson’s withdrawal agreement to be debated and voted on, but only once it had been properly scrutinised. MPs declared that a timetable which included a 31 October departure did not allow enough time for the 110-page document to be properly considered and, if necessary, amended.

As a result, Boris Johnson ‘paused’ the legislative process on his withdrawal agreement, causing speculation to mount around whether he will push for an early general election.

EU agrees to deadline extension – October 2019

On 28 October, EU leaders agreed to grant Boris Johnson an extension. This puts the official departure date back to 31 January 2020, while also enabling the UK to leave before this date if the terms of departure could be agreed by both British MPs and European lawmakers.

UK general election begins – November 2019

A general election campaign began in the UK on 6 November 2019. It was called by Boris Johnson, who was seeking to break the deadlock in Westminster and achieve a majority within the House of Commons to get his Brexit withdrawal agreement passed by MPs.

Brexit was a big talking point of the campaign, as was the NHS, childcare, the environment, taxation and spending. All of the main parties made commitments to increase spending, but they were divided over how much they would increase taxation.

Result of the election announced – December 2019

The election result was announced on 12 December 2019. The Conservatives won a majority of 80 seats, while Labour lost a few former party strongholds. The pound rallied on expectations of a Conservative win, which came from exit polls after voting stations closed.

The result handed the Conservatives a solid mandate to pursue Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal, which he said he wanted to get passed through the Commons before Christmas 2019.

MPs approve withdrawal agreement – December 2019

On 20 December 2019, MPs voted 358 to 234 in favour of Boris Johnson’s withdrawal agreement. The vote to pass was helped by the majority that the prime minister managed to win in the election, with his new Conservative MPs voting (largely) along party lines.

UK leaves the EU – January 2020

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020, initiating a transition period which will last until 31 December 2020. The transition period allows time for UK and EU negotiators to attempt to ‘roll over’ any existing trade deals between the EU and other countries, such as Canada, as well as for the UK and EU to strike up a trade deal of their own.

EU sends draft trade deal to UK – March 2020

The EU sent a draft of a post-Brexit trade deal to UK negotiators in March 2020, which left a lot of blank spaces and included a number of placeholders, but the draft did contain provisions for security, foreign policy and fisheries. The outbreak of the coronavirus made negotiators explore alternative ways to continue their discussions, including via video chat.

The draft deal also included a number of proposals, such as a joint partnership council with 16 subcommittees including one that was dedicated to a level playing field on competition, taxation, labour, social protection and the environment. Plus, it included long-term agreements over the rights of EU boats to access British waters with annual negotiations to expand or amend the provisions.

Philosophical divides begin to widen – May 2020

In May 2020, the EU’s chief negotiator Michel Barnier suggested that the UK’s demands weren’t realistic and went on to caution against a potential stalemate in negotiations. The UK had remained firm that it wouldn’t extend the negotiation period beyond the 31 December 2020 deadline, even as the coronavirus dominated headlines and consumed international leaders’ time.

A sticking point to negotiations at this stage had been EU access to UK fishing waters, with cabinet minister Michael Gove stating that the EU wanted ‘to have the same access to our fish as they had when we (the UK) were in the EU’. He urged the EU to show flexibility and remained firm that a deal could be done.

Downing Street insists that Brexit talks have not broken down – July 2020

There was mounting speculation in July 2020 that a deal wouldn’t be reached and that negotiations had largely broken down, with Downing Street officials countering that there had been neither a ‘breakthrough nor a breakdown’.

Differences over the level playing field for businesses, governance and fishing rights remained, and a spokesperson for the British prime minister stated that ‘significant differences still remain on a number of important issues’.

Boris Johnson seeks to override part of the Withdrawal Agreement – September 2020

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, the British prime minister held a virtual call with around 250 Conservative members of parliament to help him get the controversial Internal Market bill passed into UK law. The bill, if passed, would give UK lawmakers the ability to modify rules relating to the movement of goods between the UK and Northern Ireland, and it would come into effect on 1 January 2021 – one day after the end of the negotiation period.

The EU have stated that the proposed bill must be scrapped or the UK risks pushing the EU away from the negotiating table. The UK government argued that the bill is needed to protect the peace process in Northern Ireland and the country’s relationship with the rest of the UK.

Negotiations continue amid the pandemic – October - December 2020

The Covid-19 pandemic stole the headlines for much of 2020, but Brexit negotiations continued. News teams picked up on several late-night, last-minute meetings between the UK and EU negotiating teams in the run up to the official departure date of 31 December 2020 as the final details of the deal – mostly surrounding fisheries – were ironed out and settled.

The UK officially leaves the EU – 31 December 2020

At 11pm (UK time) on 31 December 2020, the UK and EU officially and legally parted ways. Leaving with a deal made the separation more gentle than it might’ve been if one hadn’t been achieved, but the relationship between the world’s fifth largest economy and the world’s largest trading bloc now has more red tape and fewer freedoms than it previously did.

1 The UK in a Changing Europe, 2018

IGA, may distribute information/research produced by its respective foreign marketing partners within the IG Group of companies pursuant to an arrangement under Regulation 32C of the Financial Advisers Regulations. Where the research is distributed in Singapore to a person who is not an Accredited Investor, Expert Investor or an Institutional Investor, IGA accepts legal responsibility for the contents of the report to such persons only to the extent required by law. Singapore recipients should contact IGA at 6390 5118 for matters arising from, or in connection with the information distributed.

The information/research herein is prepared by IG Asia Pte Ltd (IGA) and its foreign affiliated companies (collectively known as the IG Group) and is intended for general circulation only. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation, or particular needs of any particular person. You should take into account your specific investment objectives, financial situation, and particular needs before making a commitment to trade, including seeking advice from an independent financial adviser regarding the suitability of the investment, under a separate engagement, as you deem fit.

See important Research Disclaimer.