This information has been prepared by IG, a trading name of IG Markets Limited. In addition to the disclaimer below, the material on this page does not contain a record of our trading prices, or an offer of, or solicitation for, a transaction in any financial instrument. IG accepts no responsibility for any use that may be made of these comments and for any consequences that result. No representation or warranty is given as to the accuracy or completeness of this information. Consequently any person acting on it does so entirely at their own risk. Any research provided does not have regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation and needs of any specific person who may receive it. It has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Although we are not specifically constrained from dealing ahead of our recommendations we do not seek to take advantage of them before they are provided to our clients. See full non-independent research disclaimer and quarterly summary.

United Kingdom and European Union (EU) negotiators meet this weekend to thrash out a Brexit deal ahead of the European Council summit on 22 and 23 March.

Standstill transition expected

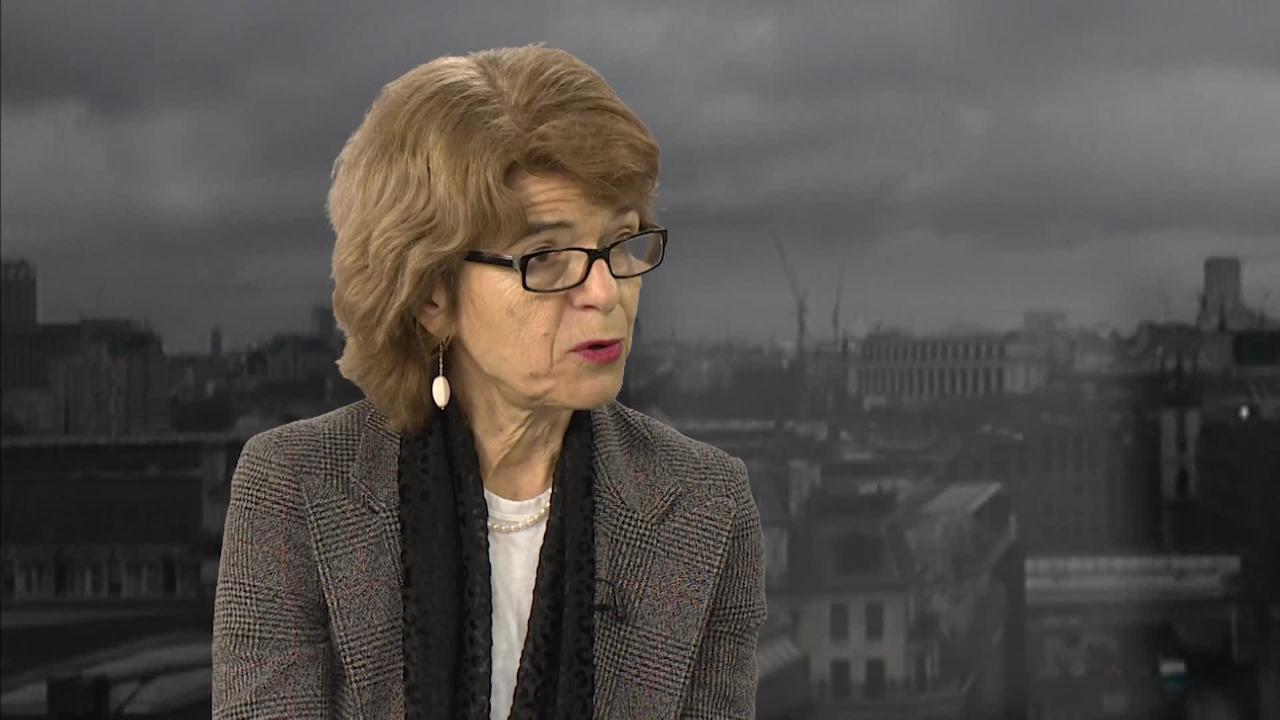

A standstill transition is likely, with the transitional period of two years to be cut. It is expected it will now run from when the UK leaves in March 2019 until the end of 2020, rather than the two years initially discussed. It is also expected that EU citizens coming to the UK will have the same rights during that period as now, with Prime Minister Theresa May conceding this point earlier this month. Vicky Pryce, board member of the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR), in conversation with IG’s Jeremy Naylor, said no solution has yet been found that satisfies the EU in relation to the UK’s only land border with the bloc, between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

The transition deal would see pretty much the status quo for the UK, as within the EU, it is part of the single market, the customs union and under the European Court of Justice. It is important to have clarity on the labour front for EU citizens here now or arriving during the transition, Pryce says.

Hard Brexit would be bad news

Jacob Rees-Mogg, a staunch Brexiteer and currently leading the odds as next Conservative Party leader, argues Mrs May should call the EU’s bluff and that a no deal World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules exit is a good alternative. Refuting this, Pryce says 99.9% of economists think that would be very bad news. ‘What you don’t want is trade that is inhibited’, she says, adding that that would completely kill the agricultural section, the manufacturing sector, and there would be no guarantee other countries would reduce their tariffs.

A so-called hard Brexit would be where the UK and EU do not reach a future trade agreement. WTO rules and agreed tariffs would then apply, and Pryce notes that business certainly wishes to stick with the customs union.

As for the financial sector, the single market is key, as without that there is no passporting. That would require re-approval by each individual EU member state for companies to operate.

Implications for growth once deal done

As to growth, Pryce says, the concerns are the consumer and investment. The consumer has been hit by the Brexit-driven fall in sterling, while wages have not climbed as expected with falling unemployment. In investment, companies need to start investing to meet demand with employment at capacity. The world economy and trade are expanding, particularly in Europe, but ‘we are leaving’. The worry is that by the time the UK does leave in 2021, the global business cycle will be turning down.